- Home

- Jayne Amelia Larson

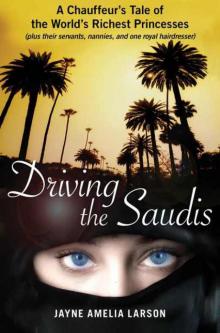

Driving the Saudis Page 23

Driving the Saudis Read online

Page 23

“I know. On the last day too. It looks like I rubbed up against the Hulk. Do you think I can get this buffed out?” I asked. “I can’t turn the car in this way. It could be thousands of dollars worth of damage. I don’t even know what kind of coverage we have. I’ll probably end up paying for this.”

“Hold please,” he said, throwing up his hand to stop my rant as he walked over to his SUV and popped the tailgate. Sami traveled with an astoundingly well-equipped vehicle in anticipation of any unforeseen emergency. He could have survived for two weeks just living off the edible contents in his car. He also had assorted power tools, several calculators, an electronic translator, and even a portable GPS satellite system separate from the car’s system in case he was stuck in the desert with a dead phone and a dead car. You could’ve probably asked him for a chain saw and he would have been able to produce one. He put on surgical gloves that he pulled from an industrial-sized box (it was a little strange that he had such a huge box of them, but he was rather fastidious). Then he grabbed a chamois rag and a small can of liquid, doused the rag, and started working on the green gash. Within a few moments, some of the paint started to come away. He doused the rag again and worked on the gash a little more. It was definitely dissolving.

“What is that?” I asked.

“Gasoline, chica.”

“You’re cleaning it with gas?”

“This is going to work but you’re going to need a lot of it,” he said. “Use this chamois and go easy. Here’s some fresh gloves. Go get some more gasoline, and start scrubbing.” With a few well-placed firm taps, he popped out the three-foot-long dent with a rounded hammer that he also kept with him. The car was going to be okay. I was so relieved that I grabbed him and hugged him. He didn’t hug me back but instead turned away sheepishly when I let him go, just as my teenage nephew does when he’s not sure how to respond to my affection. He’s pleased that I’ve offered it, but he can’t reciprocate.

“Did they take care of you?” he asked me.

“I sure hope so, but I haven’t counted my tip yet. I wanted to wait until they were gone.”

“Yeah, me too, but I couldn’t wait.”

“You do okay?” I asked. He didn’t say anything but walked back to his car smiling.

“All right! Praise be to Allah!”

I knew that he really needed the cash to look after his mom, and a decent amount of tip money in addition to his pay could carry them through several months. She had recently been shot while coming home from the grocery store. It was a gang-related wild shot fired from a moving vehicle a couple of blocks away from where she was walking. Luckily, the bullet didn’t hit any major organs; it just ran straight through the fleshy part of her upper arm. But she was severely traumatized by the incident and was now afraid to leave the house.

I spent the next hour rubbing off the paint at a nearby gas station. Sami’s tricks worked like a charm. As I labored away at the green mess with the smell of fossil fuel filling my nostrils, I couldn’t help but think: Now I’m even cleaning with gasoline. Next thing you know I’ll be bathing in it, maybe even drinking it. Thanks so much, I’ll have a 93 octane please, up, bone dry. Lose the fruit.

—

Before I turned the rental car in, I pulled into a shady Beverly Hills alley and parked. I was ready to count the tip money. I took the envelope out of my pocket and opened it.

Inside was a stack of hundred-dollar bills, as I knew there would be, and crisp as if they’d never been handled. They almost snapped as I counted them. But there were only ten.

One thousand dollars.

I suddenly couldn’t hear anything except the beating of my heart and the distant sound of a leaf blower in one of the gardens off the alley. I paused for a moment to collect myself. Then I counted them again and again, hoping that I’d make a mistake, that the bills had somehow stuck together, praying that perhaps more were hidden somewhere in the envelope.

My tip was only one-fifth of what most of the other drivers had received, and yet I’d done at least ten times the work. Do they not think I’m as valuable? I wondered.

Later, I asked my friend to translate the envelope for me. It said Maysam’s Driver. I thought that was odd. I was fond of Maysam, and I was happy to be associated with her, but only one name on the envelope implied that I had been assigned to one person when I had actually driven so many people, including Fahima, Princess Aamina, Princess Rajiya, Malikah, Asra, and of course the hairdresser as well as many of the servants. I drove to Palm Springs and back every night for almost three weeks straight. I was the go-to all-around girl. I scored twenty-seven bottles of Hair Off in a five-hour time frame. Who else could have done that?

My name wasn’t written on it either, even though I thought the colonel had asked my name to confirm that he was giving me the correct envelope. But I am sure he must have known of most, if not all, of my duties and had probably even assigned some of them even if they were always conveyed via the security on the twelfth floor. What the hell? I thought. Maybe they don’t even know who I am or what I’ve done.

To whom could I complain? The family was already 30,000 feet up in the air in a $300 million getaway vehicle. And even if I had mustered up enough courage to speak, what could I have said? Listen here, missy princess, you should be ashamed of yourself. Hasn’t all that beauty and privilege taught you something?

Up until the very last moment, a little part of me was still holding onto the promise that the world is a meritocracy and that my hard work, conscientiousness, and dedication would be recognized. But I understand now that that was just crazy thinking. Nobody gave a shit.

Now as I track back through the experience, I see that it couldn’t have turned out any other way. I was a woman, and I’m sure that they thought I didn’t need or deserve the same money as a man who had the responsibility of taking care of his family. It didn’t matter what the actual circumstances of my private life were. As a woman I would be taken care of; that is assumed. In fact, I had even invented a husband who was fast on the road to recovery, who no doubt would soon be able to provide for me again. I had told them Michael was on the mend when I should have killed him off. Maybe that would have generated some cash sympathy.

My head was spinning with fatigue and disappointment. I sat in the car in silence for over twenty minutes trying to get it up to turn on the ignition, drive away, and get on with my life. Several gardeners tending to the estates adjacent to the alley looked at me with curiosity as they emptied their refuse in the receptacles that lined the alley. One nice old man knocked on my window. “Miss, miss. You okay, miss? You need help?” I waved my hand at him in thanks.

In my angst, I had crumpled up the hundred-dollar bills and thrown them on the car floor, where they were now wedged between the back and front seats, the carpet and the console. It took me several minutes to find all ten of them, smooth them out, and put them back in the envelope.

Later I figured out that I had driven over 10,000 miles in seven weeks—sometimes 400 miles a day—on average eighteen hours a day, seven days a week for seven weeks straight. And I did it willingly. I thought I would be rewarded.

I did it for the money.

—

When I could finally see straight enough to drive, I turned in the rental car and was relieved when nobody said a peep about the condition of the vehicle. I asked the Regent courtesy car to drop me off at the Beverly Hills Hotel, a short distance up Rodeo Drive. My friend Lorelei was waiting there for me. She had won a load of gift certificates in a raffle and was having a full day of pummeling and buffing at the spa and wanted to treat me to a meal in the Polo Lounge her last evening in Los Angeles, before she moved back east to start a new life far away from the entertainment business. She’d had enough of the trials and tribulations. She’d come to Los Angeles just after I did and worked at her career with a diligence that would frighten a beaver. But she soon came to realize that she didn’t have it in her to compete with talking dogs, singing puppets, an

d former Playboy models for the role of a twenty-one-year-old nuclear scientist.

The hostess seated us at the front part of the Polo Lounge, in a brushed velvet banquette near the piano, and I looked around the dark-green clubroom. The bar was jammed with lively and satisfied-looking people. All around me, well-dressed men and women were sipping from long-stemmed martini glasses, nibbling on spiced nuts and wasabi dried peas, and sucking down kumamoto oysters. The lights twinkled, and the shadows of the people bounced along the pictures of polo players lining the bar wall. A woman at the piano softly played smooth standards; an older couple was necking, ensconced in one of the comfy pale green banquettes, next to us. The man crooned into the woman’s ear, “Day and night, you are the one.”

“Please have whatever you like; it’s on me,” Lorelei said. “We deserve it.”

I shook my head in confusion. Only hours before I had been a lowly chauffeur, and now, in the same black Calvin Klein suit that I had worn all day pinned at the waist, I looked up at the debonair white-haired waiter wearing a white double-breasted jacket, an elegant little Five Star Award pin in his lapel, and ordered a forty-dollar Truffled Kobe Burger and a glass of Napa Valley cabernet, and watched him adjust the salt and pepper shakers on the table as a symbol to the rest of the staff that he had taken our order. Then I smiled at my friend and listened to her chime on about the endless possibilities of the new life ahead of her. She was rosy-cheeked and clear-eyed after her beautification treatments and said she couldn’t wait to reinvent herself. “What the hell,” she said. “That’s what life is all about. Rebirth, re-creation, regeneration. And by the way, the burgers here are the best in the city! I’m so glad you ordered one. I want a bite.”

From my seat on the banquette, I could see directly through the lounge doorway into the brightly lit hotel beyond. I watched uniformed hotel maids and housemen, pink-shirted valets, and black-suited chauffeurs trudge by, making their way silently down the long plushly carpeted hallway leading to the service elevators and the hotel’s small private garage where the most expensive cars are housed: the million-dollar Maybachs and Rolls-Royces. Periodically one of the workers would glance at the lounge door, his or her attention pulled by the music and clinking of glasses, listen for a moment, and then slowly look away while moving on. Occasionally I would catch someone’s eye and smile.

As I brought my wineglass to my lips, I noticed that my hands still smelled like gasoline even though I had cleaned them several times since I’d polished the Hulk residue off the car. After a few minutes, I excused myself to go wash them again in the hotel’s football field–sized ladies’ room at the far end of the lobby. I used the soft terry towels to scrub my hands and face, and then freshened up my lipstick in the panoramic wall of gilded mirrors. From every angle, I was a fright. My parched hair had whipped up into a cotton candy mess at the top of my head from driving in the convertible without my cap. I knew it would be weeks before I’d be able to get a comb through it. My eyes were sunken and glassy, and my skin looked like an 8-ton truck had run over it after it had lost a few of its tires. I pinched my cheeks to brighten them up a bit, then quickly skedaddled.

The lobby entrance was jammed with women draped in satin, taffeta, and tulle and rushing tuxedoed men who almost ran me over as I exited the ladies’ room. There was a wedding celebration in the hotel’s grand Rodeo Ballroom, and I heard murmuring that the couple was about to arrive. I threaded my way through the beautiful people and sat down on one of the pink tufted lounge sofas to admire the hustle and bustle of the festivities, hoping to get a peek at the bride. The lobby air was heady with the powerful scent of the tiger lilies in the towering floral arrangements placed throughout the room, competing with the expensive French perfume and Italian cologne wafting from the wedding partyers. Soft diffused light glowed in the monumental gold-domed crystal chandeliers.

I watched a woman in a long gold lamé gown catch her heel in the carpet, stumble, and then drop her gold Chanel clutch purse as she hurried to the ballroom; the clutch bounced a few feet away along the thick green and pink carpet when a lobby attendant just behind her graciously retrieved and proffered it to her. She glared at him for a moment and then snatched it back without thanking him, as if he had tried to make off with it and she’d caught him. The attendant stood there for a second and then walked away, laughing to himself. I tried to let him know that I had seen what had happened, but he moved away too quickly to go about his work, and I was too tired to chase him.

I called Mr. Rumi from my cell phone.

“They’re gone,” I said.

“Wow, I thought they’d never leave. You okay?”

“I’m glad you answered.”

“You want me to come get you?”

“No. But I’d like to see you later. I’m at the hotel with Lorelei, and I doubt I’m going to last long.”

“Call me when you want to leave. I’ll drive you home.”

“That sounds really nice. It’ll be nice to be driven,” I said as I hung up. I had no idea whether I wanted to spend the rest of my life with Mr. Rumi, but I was more than happy to let him drive me around for a while.

More wedding partyers streamed by me, but there was still no sign of the bride. Lorelei came out to search for me and tell me that my forty-dollar burger was getting cold.

“Why are sitting out here? Are you all right?” she asked. “You look like you’re lost.”

I smiled. “No, I am fine. Thanks. I’m just taking it all in.”

Epilogue

I hated being a chauffeur. The work was demeaning and exhausting, I felt trapped by the uniform and the confines of the car, was humiliated and disturbed by the unseemly behavior that seems to go with the job, and lost sight of any possible bright future when I was behind the wheel. The very place where I was supposed to be in control afforded me little autonomy or any comfort of command. Every now and then, though, something happened that restored my faith in life, my faith in mankind, and my faith in my future.

One morning, I had a pickup at the Hollywood Renaissance Hotel. The call was an A.D., which meant “as directed by the client” and could last all day or night, destinations and time frames unknown. If it were an evening call, that usually meant I’d be driving out-of-town businessmen to the Lakers’ game and then to a slew of strip bars, maybe we’d hit a Koreatown massage joint around dawn, then I’d drop them off at a private plane for a 10:00 A.M. wheels-up. But I’d never been on a daytime A.D. before, so I had no idea what it might entail.

The Renaissance is not a luxury hotel; it’s a 140,000-square-foot monstrosity behind the Kodak Theatre frequented by tourists who want to be close to the Hollywood Walk of Fame and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! and who likely can’t afford the Beverly Hills Hotel or even the Beverly Hilton but still want to feel as if they’re part of the Hollywood elite. It was a pickup address that did not inspire hopeful anticipation. I only knew that it was going to be a long, probably achingly boring day, and I prayed that it wouldn’t be awful.

As required, I arrived at the hotel fifteen minutes before the appointed pickup time, and my client was ready and waiting at the hotel entrance. I recognized him right away. Garrison Keillor climbed into the car without any fanfare, and we started off for Torrance, California, where he said he had a book signing. At first he was quiet on the long drive. He apologized for not conversing and said he was tired from his previous night’s performance at the Hollywood Bowl, but after some time, he grew curious about me, and we talked about art, literature, and independent filmmaking. His voice was the same unusually deep baritone that I often heard on the radio as I waited in the LAX limo parking lot holding area for delayed planes on long, lonely Saturday afternoons.

He said he would have bet a hundred dollars that I belonged in the back of a limo and not the front, and that made me laugh out loud. I had ridden in a lot of limos and had even gotten the bright idea to be a chauffeur when I was sitting in the back of a limo. He was gentlemanly, almost courtly, an

d asked me many questions about who I was and what I thought about: How did a lady like me end up driving a limo, for God’s sake? What did I do in my real, nonchauffeuring life? What did I dream of always doing but hadn’t done yet? He seemed genuinely interested in me and my answers; I was so delighted that I almost drove off the freeway.

He mentioned the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus and his belief that the universe is in a constant state of change—that only by hitting rock bottom could an individual experience great change, and that all vital things come into being as a result of obstacle, strife, and effort. My ears perked up at this. Finally, he said, “Out of discord comes the fairest harmony.” I found this strangely comforting, and as he spoke, I could feel my body relax, in a small quiet way, as if every cell stilled itself for an instant and then exhaled a soft little sigh. His voice lulled me into a happy and alert repose. And in that very moment, a tiny glimmer of hope sparked in my heart that things might get better.

We arrived at a mall bookstore in Torrance, and he went in to give a lecture. I stood in the back and listened and laughed along with the crowd of hundreds to see him; he winked at me when he saw I was there. He spoke for an hour or more and then began to sign books and converse with people. I saw that he really spent time with each person; many were fans who just wanted to fawn, but many wanted to share their personal stories with him, and he listened patiently and attentively. He was never abrupt. Sometimes he even consoled people. From a distance, it looked like an older man wept on his shoulder for a short while, but maybe they were just sharing a memory. After several hours, I hunted down the store manager and got some tea and a muffin for him. I set them on a table near where he was standing. “Oh, my dear, thank you so much,” he said. “I am famished and parched.” He continued to sign books throughout the rest of the afternoon, standing all the while, until no one was left in line; many fans had been waiting for hours with stacks of books for him to sign. I wandered around the bookstore and saw that there were titles by him in the children’s section, the nonfiction section, the fiction section, and the poetry section. He even had a book of jokes. “What’s green and hangs from trees?” (Giraffe snot.) I hadn’t realized he was so prolific.

Driving the Saudis

Driving the Saudis